Web scraping is frequently used when no suitable public data can be found in a structured format. Unstructured or semi-structured data served on static websites or web applications can be scraped programmatically and structured for analysis. But before reaching for your favorite web scraper you should first check for hidden, but publicly-accessible APIs used by some websites to fetch data client-side to be rendered into HTML. Using these APIs to gather data can be highly beneficial in several ways:

- Less overhead: you can avoid downloading unnecessary content, which significantly reduces response time

- Already structured: many API responses return well-structured JSON data

- More data: API responses may contain more information than what is rendered in the HTML

Toy problem

Let’s say you want to know how used car prices vary with mileage in your geographic area. You can’t find an open dataset with the characteristics you need (e.g., recently updated, covers your geographic region) so you decide to go to an online used-car retailer like CarMax and scrape some data1. Let’s solve this problem the normal way first. We’ll then assess this approach and find a hidden API that will allow us to tackle the problem much more efficiently.

The hard way

You read up on some BeautifulSoup tutorials, fire up your browser’s developer console, take a look at the HTML from a CarMax search page, and write a small function to scrape some key details for you:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def get_carmax_page_web():

"""Get data for a page of 20 vehicles from the CarMax website."""

# request HTML content from search page

headers = {'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_11_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/50.0.2661.102 Safari/537.36'}

page_url = 'https://www.carmax.com/cars?location=all'

response = requests.get(page_url, headers=headers)

# extract vehicle list from HTML

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

vehicles_raw = soup.select('div.vehicle-browse--result--info')

# extract relevant data points from vehicles section of the HTML

return [

dict(

price=vehicle.select_one('span.vehicle-browse--result--price-text').text,

mileage=vehicle.select_one('span.vehicle-browse--result-mileage').text,

**{key: value for key, value in vehicle.attrs.items() if key != 'class'}

)

for vehicle in vehicles_raw

]

Note there are three steps here, each of which involves significant execution time or development time:

- request HTML: takes about 1.2 seconds response time

- extract relevant content from HTML: takes about 0.6 seconds execution time

- parse data: minimal execution time, but requires substantial development time 2

The smart way

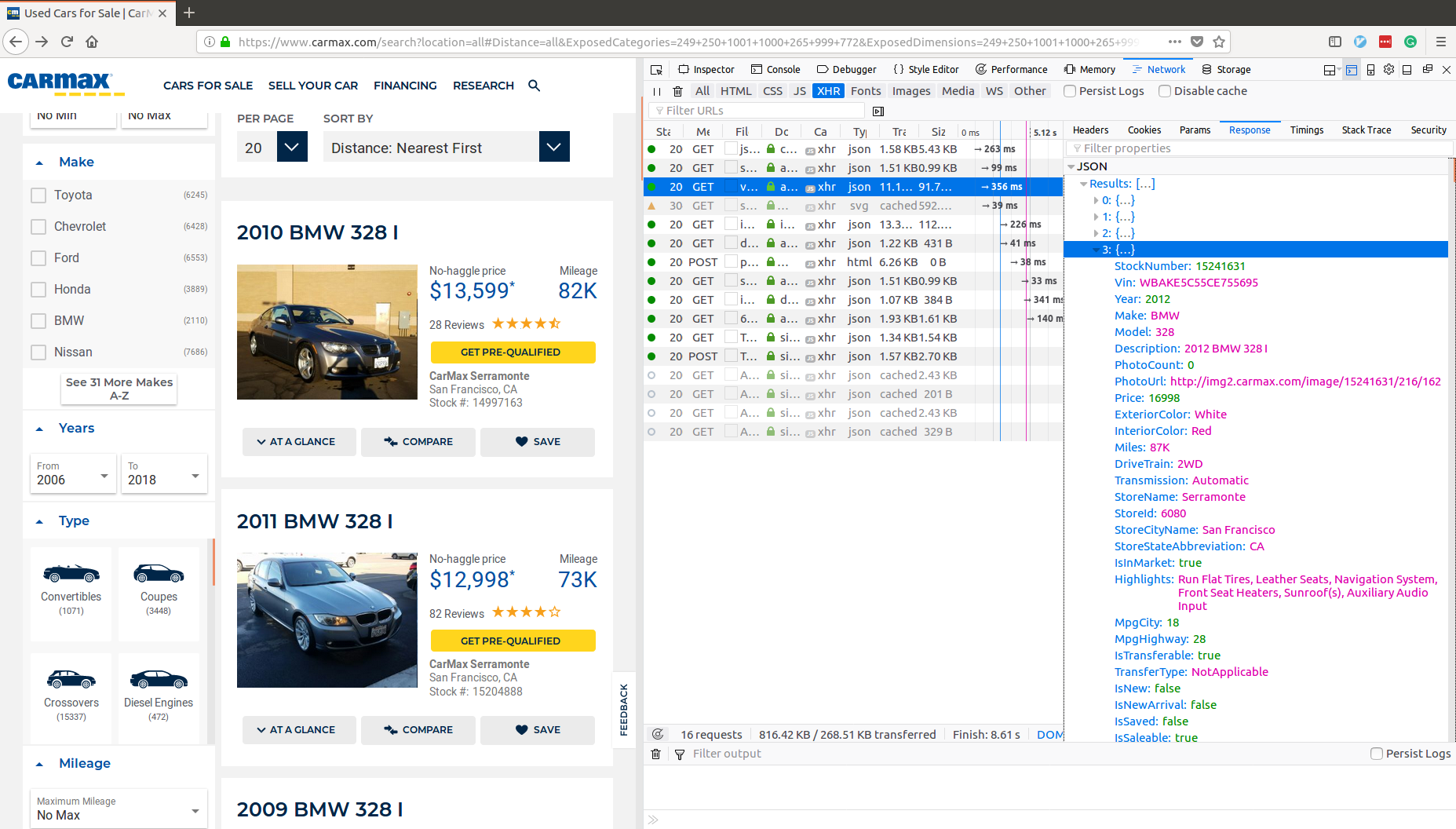

Many applications will load code onto your browser’s client session, and that code will make API requests to load data from another server directly to your browser. Luckily for us, most modern browsers allow you to easily monitor these requests. In Firefox, you can monitor XHR requests by opening the web developer console and going to the network tab. Once we load the page, we can see each request made, and what response was received.

Next, we notice there is a request made to this endpoint: https://api.carmax.com/v1/api/vehicles. Opening the JSON response, we see there is a Results key, and the corresponding value is a list of vehicle objects like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

[

{'AverageRating': 4.833,

'Cylinders': 6,

'Description': '2015 Acura RDX AWD',

'DriveTrain': '4WD',

'EngineSize': '3.5L',

'ExteriorColor': 'Black',

'Highlights': '4WD/AWD, Leather Seats, ...',

...

{'AverageRating': 4.833,

'Cylinders': 6,

'Description': '2015 Acura RDX AWD',

'DriveTrain': '4WD',

'EngineSize': '3.5L',

'ExteriorColor': 'Brown',

'Highlights': 'Technology Package, Power Liftgate, ...',

...

},

...

]

All we have to do to get these pre-parsed results programmatically is to emulate the request our browser just made – here it is in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def get_carmax_page_api():

"""Get data for a page of 20 vehicles from the CarMax API."""

# make a GET request to the vehicles endpoint

page_url = 'https://api.carmax.com/v1/api/vehicles?apikey=adfb3ba2-b212-411e-89e1-35adab91b600'

response = requests.get(page_url)

# get JSON from requests and return the results subsection

return response.json()['Results']

Note this code is much more concise than before, as the response is already structured for us and we no longer have to identify specific data points from a large blob of semi-structured text. On top of this, we are no longer asking the server to send us data we aren’t going to use so the response time is significantly faster, clocking in at a mere 0.2 seconds:

Lastly, the API response comes with significantly more data per vehicle: StockNumber, Vin, Year, Make, Model, Description, PhotoCount, PhotoUrl, Price, ExteriorColor, InteriorColor, Miles, DriveTrain, Transmission, StoreName, StoreId, StoreCityName, StoreStateAbbreviation, Highlights, MpgCity, MpgHighway, IsTransferable, TransferType, IsNew, IsNewArrival, IsSaved, IsSaleable, IsSold, Cylinders, EngineSize, AverageRating, NumberOfReviews, NewTireCount, LastMadeSaleableDate, LotLocation, Links. When scraping the HTML page, we found significantly fewer fields for more work: price, mileage, data-vehicle-make, data-vehicle-model, data-vehicle-price.

Recap

To recap, by doing things the smart way – by finding public but hidden APIs through our browser to scrape data instead of parsing HTML – we were able to cut our execution time down by nearly 90%, save significant development time, and get more data per vehicle. So remember to always look before you scrape!

-

It’s against the terms of services for many sites to scrape their data; I read the CarMax terms of service, and it’s not entirely clear that ad-hoc scraping is prohibited, so I’m not officially recommending you do this. ↩

-

On top of the upfront development time, the HTML content structure is likely to change over time leading to significant maintenance time. ↩